At the July 7, 1887 meeting of the City Council, a number of citizens presented a petition requesting that the council establish and maintain a public library.

On September 14, 1887 the Highland Park City Council adopted an ordinance for the establishment of a tax-supported public library and appropriated $260 annually for its maintenance.

Some people believe that the first home of the public library was MacDonald's Store. However, when the library opened on April 6, 1888, it shared space with the City Council in quarters rented for the council's use. At that time the City Council was renting its meeting place from Frank Hawkins, and met on the first floor of a store building formerly occupied by Charles A. Kuist Hardware. It was located just east of MacDonald's Store on the north side of Central in the block between St. Johns & Sheridan Road.

Books began circulating from the library on April 7, 1888. There were approximately 400 books in the library's collection and each borrower was allowed 1 book for a 2-week loan period. The library was open on Monday evenings from 7 to 9 p.m. and on Saturdays from 3 to 5 p.m. and from 7 to 9 p.m. The first librarian was Miss Marsalene Green. Miss Green received a salary of $75 per year, which was paid by subscription; she served as librarian for just a few months before her untimely death. Miss Anna Obee was appointed her successor.

In July 1889 the City Council graciously invited the Library to share space in the newly constructed city building. The space allotted to the library was the west half of the rear of the City Clerk's office. Two years later, the city jail was moved to a separate building, and the library doubled its size by expanding into the old jail area.

In May 1891 Mrs. Mary Ann Jennings became the third librarian, a position she held until 1913. Under her leadership, the library saw steady growth. The collection grew from 400 books to over 7,000. The Library began publishing a catalogue of the collection, copies of which could be purchased for 10 cents. The Library didn't use the Dewey Decimal Classification System until 1903 when Miss West, "an expert in modern library methods," was engaged to prepare a new catalogue. Before 1903 books were located in the following general sections: Fiction; History, Biography, and Travel; Juvenile; The Sciences; Poetry; and Art, Essays and Miscellany. Within the sections, each book had a number indicating its physical location.

In May 1891 Mrs. Mary Ann Jennings became the third librarian, a position she held until 1913. Under her leadership, the library saw steady growth. The collection grew from 400 books to over 7,000. The Library began publishing a catalogue of the collection, copies of which could be purchased for 10 cents. The Library didn't use the Dewey Decimal Classification System until 1903 when Miss West, "an expert in modern library methods," was engaged to prepare a new catalogue. Before 1903 books were located in the following general sections: Fiction; History, Biography, and Travel; Juvenile; The Sciences; Poetry; and Art, Essays and Miscellany. Within the sections, each book had a number indicating its physical location.

With a growing collection, it was soon evident that larger quarters were desperately needed. In the spring of 1900, the library board purchased the Young Men's Club House (commonly known as the Atheneum, located on Sheridan Road just north of Central) at a cost of $2,000 ($1,000 of which was contributed by the City Council).

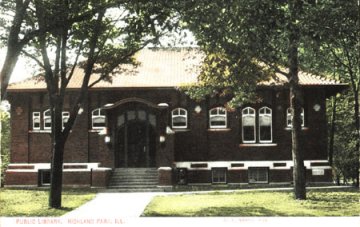

Here the library resided for five years, but by 1903 a movement was already underway advocating the construction of a new building. Mayor Robert G. Evans appointed a commission made up of aldermen, the city attorney, and members of the Woman's Club to confer with the Library Board. The commission contacted Mr. Andrew Carnegie for a financial donation to construct a new library. Mr. Carnegie had many philanthropic interests, but public libraries were the major beneficiaries. Between 1886 and 1919, over 1600 Carnegie library buildings were constructed. Mr. Carnegie was willing to donate $10,000 for the construction of a library building in Highland Park, provided that the city owned the site.

Here the library resided for five years, but by 1903 a movement was already underway advocating the construction of a new building. Mayor Robert G. Evans appointed a commission made up of aldermen, the city attorney, and members of the Woman's Club to confer with the Library Board. The commission contacted Mr. Andrew Carnegie for a financial donation to construct a new library. Mr. Carnegie had many philanthropic interests, but public libraries were the major beneficiaries. Between 1886 and 1919, over 1600 Carnegie library buildings were constructed. Mr. Carnegie was willing to donate $10,000 for the construction of a library building in Highland Park, provided that the city owned the site.

The Atheneum site was deemed unsuitable for the new library, and, even with the sale of the library building, the Library Board did not have sufficient funds to purchase other available sites. Finally, in the spring of 1905, the Library Board received an offer from Mr. Arthur C. Thompson, of Brookline, Massachusetts. He offered to give the city a piece of property upon which to locate the new library. Although not a resident of Highland Park, Mr. Thompson owned an extensive amount of business property in the community. The lot that he gave to the library was located on Laurel Ave. one block south of Central Street, and just east of St. Johns Ave.

The Chicago architectural firm of Patton and Miller was selected to design the new library. Eminently qualified for their commission, Grant Miller and Normand Patton had designed over 100 library buildings during their partnership from 1901 to 1912.

The Highland Park News-Letter (November 11, 1905, p. 4) described the plans for the Carnegie library. "The building is 60 feet front by 40 feet deep, one story high, with basement for a fine assembly room....The roof is to be of tile with best metal gutters. It will be lighted with electricity and gas, heated by hot water, interior wood work of oak, hall floors in mosaic. Exterior Bedford cut stone trimmings, and Portsmouth Ohio glazed paving brick. All fixtures will be of the best, up-to-date in every respect, and the building complete and ready for occupancy will represent an outlay of $17,000."

Andrew Carnegie eventually donated $12,000, sale of the Atheneum building netted $4,361. Through a special appropriation, the City Council provided $1,500. The Library Board provided $32.27 to the final cost of the building $17,893.27.

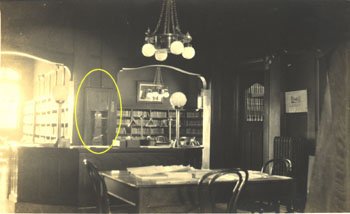

The clock in this picture (left) of the interior of the Carnegie library was donated by the High School class of 1907 and is still located in the library.

The clock in this picture (left) of the interior of the Carnegie library was donated by the High School class of 1907 and is still located in the library.

After the building was completed, the Library Board turned its attention to service. Library hours were increased to three hours every week day afternoon and one evening each week. In May 1907 the Library Board passed a motion granting the librarian a vacation and authorizing the president to engage a substitute during the time the librarian was to be absent. In July 1907 the Library offered its first story telling hour. It was for children between the ages of five and nine and proved quite successful. The increases in service and staff required an increase in tax revenues to maintain the Library. The appropriation was raised to $1,500 per year. Mrs. Jennings received a salary of $400 per year and her new assistant, Miss Annie McKenzie, was paid $20 per month. In 1912, a second assistant, Miss Nita Anderson, was hired at a salary of $10 per month.

The Library made additional changes to service in the first decades of the 1900s. It converted to "open shelves," allowing library users to walk into the book stacks and select their own books. Prior to that time, patrons called for a book by writing its shelf location number on a slip of paper, which was handed to the librarian. The term "call number" is still used to refer to a book's shelf location.

Another change for the Library was the addition of a telephone around 1915. This allowed residents to contact the Library from their homes (if they had telephones). In 1915 Highland Park had around 5,000 residents, but only about 1,000 had telephones.

In no time at all the Carnegie library was too small to handle the growing collections and services of the library. In 1914, the Board began purchasing surrounding land with an eye to expanding the building. Plans were delayed with the outbreak of WWI and were considered again in 1920 and 1924 but each time the need had increased even more, and plans for additions never seemed entirely adequate.

The crowded conditions forced the Board to relocate the children's room to the basement in order to provide more space for children's books. The former children's room was converted into a reference room. With a separate children's area, it was necessary to hire a children's librarian. In September 1925, the Board hired Mrs. Eva Crozier on a half-time basis at a salary of $60 per month.

By 1927 it was evident to the Board that the Carnegie library was inadequate and that only an entirely new library would do. The population of Highland Park, just 4,209 in 1910, had grown to approximately 10,000 by 1927. The number of books increased from 6,658 in 1910 to 16,773 in 1927.

When the head librarian, Mildred Crew, resigned in November 1926, the Board made a noteworthy decision - to hire only librarians with college and graduate library school training. To attract a capable, well-trained person, the Board decided to offer a starting salary of $2,700 per year. Cora Hendee was the library's first professional librarian. She arrived in 1927, just in time to assist the Board in planning for a modern library building. She established the historical archives, which includes the photographs that accompany this history. She began a regular column in the local newspaper to feature library events and new titles. For the first time, under her direction, reference and research services were defined as an integral function of the library. She lobbied the Library Board to maintain a steady appropriation for new books despite the onset of the Depression. In 1927, the year she arrived, the Library had 16,773 books. When she left in 1935, there were 30,221. The Library circulated 45,676 items in 1927 and 122,087 in 1935.

In 1928 the City Council proposed a levy increase spread over 7 years to raise the estimated $150,000 to build the new library.

The Chicago architectural firm of Holmes and Flinn (Morris Grant Holmes and Raymond W. Flinn) designed the original modified Gothic style structure built of Wisconsin limestone with Indiana limestone trim. The new library was dedicated on Sept. 20, 1931.

In 1935, Miss Hendee hired a new children's librarian, Inger Boye. Mrs. Boye served as children's librarian for 29 years. Her story hours, summer reading programs, school visits, and personal attention created a lasting image in the minds of many small children. In 1975, a room in the children's department was named for Mrs. Boye. Story times remain an important introduction to books and reading for small children. Each year the youth librarians visit classes in all the Highland Park elementary schools. They also host class and pre-school visitors at the library. The Summer Reading Program allows children to maintain their reading skills during the summer and offers games and prizes for all participants.

In 1935, Miss Hendee hired a new children's librarian, Inger Boye. Mrs. Boye served as children's librarian for 29 years. Her story hours, summer reading programs, school visits, and personal attention created a lasting image in the minds of many small children. In 1975, a room in the children's department was named for Mrs. Boye. Story times remain an important introduction to books and reading for small children. Each year the youth librarians visit classes in all the Highland Park elementary schools. They also host class and pre-school visitors at the library. The Summer Reading Program allows children to maintain their reading skills during the summer and offers games and prizes for all participants.

Although the Library survived and thrived during the Depression, it was not so fortunate during the war years. Rationing was imposed due to shortages of various kinds. The shortage of fuel oil caused the library to close on Mondays beginning in 1942 and for the entire month of April 1943. The Library also faced staffing shortages, as employees were able to find higher paying work in war industries.

Following the war, the Library still faced a shortage of funds and staff. To aid the Library's fundraising efforts, a Friends of the Library organization was founded in May 1947. Over the years the Friends group has aided the Library in countless ways with funds to purchase books, records (the Friends started a phonograph collection in 1948), art prints (started in 1965), equipment, special programs, and for publicity efforts (the Friends publish the Library's newsletter The Laurels, first issued in 1968).

Joseph Pollock became head librarian in 1958. His first years saw many innovations. These included an extended loan period from 2 weeks to 3 weeks for most materials, and the option of placing reserves on materials by telephone rather than having to appear in person. A curbside book return, known as an "auto page" was installed. A full-time, professionally trained reference librarian was hired.

Over the years, the collections of the Library continued to grow and space for children's materials was particularly inadequate. In 1960, the Library Board decided to build an addition on the west side of the existing library. Bertram Weber was hired to design what is now known as the Children's Wing in the same modified Gothic style of the original building. The cost of this addition was $121,200.

The relative prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s allowed the Library sufficient funds to develop particularly excellent collections. In 1971 the Library had 104,346 books and more than 200 magazine subscriptions. The growing collections and population and the heavy use of the Library necessitated yet another addition. In 1976 a modern adult wing (20,000 sq. ft.) designed by the firm Wendt, Cedarholm & Tippens was added to the south of the original building.

Jane W. Greenfield was appointed Executive Director in 1987. Building improvements and computer technology developments were early priorities. Remodeling to improve access for people with disabilities was completed in 1989 and was followed by renovation plans.

In 1991, a major renovation of the building upgraded heating, ventilation, and electrical systems, and redesigned space layouts in response to changing use patterns. In 1998, the lower level public meeting room and auditorium were remodeled to improve lighting, ventilation, and access. In 2000, the front entrance of the library was redesigned to improve safety and accessibility.

New collections of videos, compact discs, DVDs, CD-ROM titles, and electronic and digital resources were added as they became available.

Computer technologies developed especially rapidly during the 1990s. Computerized information sources began appearing at the library in the mid-1980s. In 1984, the Library replaced its Gaylord book charging machines with an automated circulation system. The card catalog was automated at the same time. By 1989, patrons could access the computer catalog through a dial-in telephone connection from their home computers. In 1996, a Windows version of the computer catalog was introduced and was available via the Internet. In 2000, computer catalog software was installed to give patrons access to their Library patron records via Internet connection. The software allows patrons to renew and reserve titles.

In 1986, the first subscription to an online information database was purchased. Additional computer information sources and CD-ROM titles were added, and computer labs were established for children and adults. In 1996, the Library began providing Internet services. A Library web site was created with access to subscription databases provided by the Library and with links to World Wide Web information sources. In 1998, the Library created a "gateway" web site to community information to provide an index and links to community web pages.

In 2002, Jane Conway joined the staff as Executive Director. Among her initiatives was restoration of a historic library sign that had been designed by artist and former Library Trustee, Rudolf Ingerle in 1940. The sign was returned to its original location on the southeast corner of St. Johns and Laurel Avenues.

The Library inaugurated the 21st Century with the publication of Books that Matter: A List for the Millennium. A compilation of titles submitted by Highland Park readers, the book lists a cross section of popular and classic titles for children and adults. It demonstrates the enduring value of reading, and the vital role of a public library for the residents of Highland Park.

Source: Frooman, Mary E. THE HISTORY OF THE HIGHLAND PARK PUBLIC LIBRARY (June 1972)

Additional information compiled by Julia A. Johnas.